|

1947 Motorola Model 67-X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

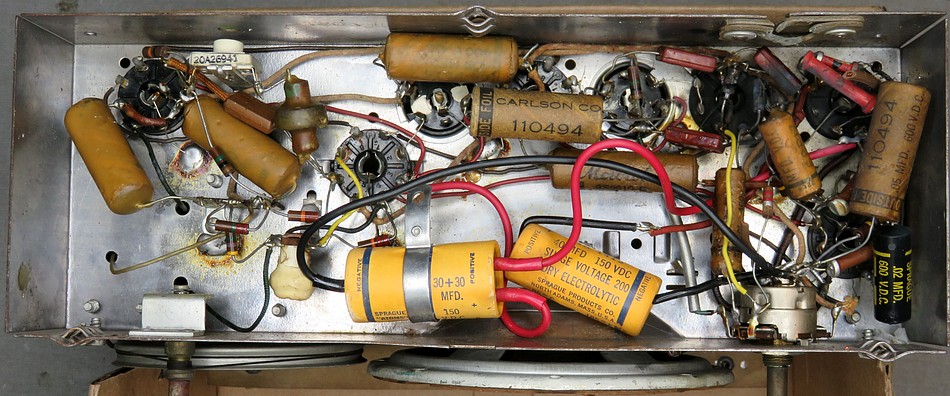

Inspection of the chassis. The first thing we

see, at the bottom center of the photo, is a large capacitor

flopping around. IT HAS A METAL BRACKET ON IT! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

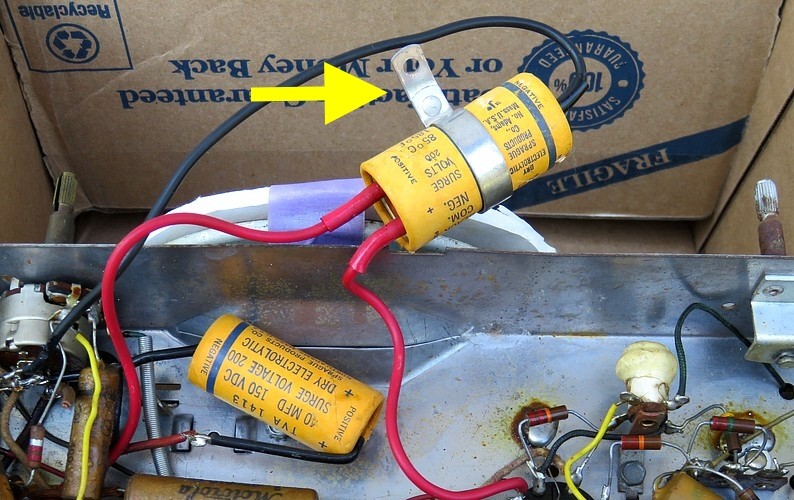

When the radio was

turned over, the metal bracket had wedged itself between two of the

pins on a tube socket, shorting them out. Apparently, a

previous "repairman" relied on GRAVITY to keep the bracket out of

the circuit. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The date stamped on the radio. 1947 was the year

Galvin Manufacturing Corporation officially changed their name to

Motorola, Inc. The brand name "Motorola" had been around since 1930

when Paul and Joseph Galvin began manufacturing car radios. The car radio

had been invented by William Leer and Elmer Wavering, then perfected

by them and Paul in Galvin's shop.

The radio above was probably manufactured in Chicago, Illinois. (In

1948 Motorola moved to a 185,000 square foot manufacturing facility

in Quincy, Illinois.)

The set contained five Sylvania tubes and an RCA audio

output tube.

The Sylvania tubes tested good except for the 14B6 (Detector and

Automatic Volume Control). The RCA 35A5 audio amp couldn't be

tested. There was no listing on the tube tester. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

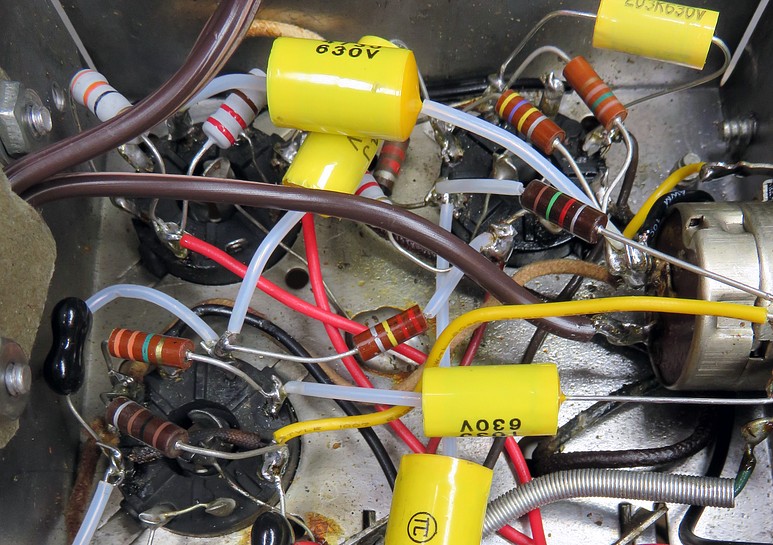

This radio was repaired in the past. From the

looks of the capacitors, it was a long time ago. It seems the

repairman didn't use any solder and just reheated whatever was

already there.

Two replacement capacitors are wax

coated Stromberg Carlsons; two are paper Stromberg Carlsons with

no wax. Two are wax coated made by Sprague and one is a plastic

Sprague. The craftsmanship (or lack of) shows that at least three

people worked on this, probably four, with the later addition of the

plastic Sprague capacitor.

Finally, there was the guy who replaced the AC cord and ruined the

radio. After working on this radio, I can say that the fact that he even tried to

replace the cord is a testament to his courage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

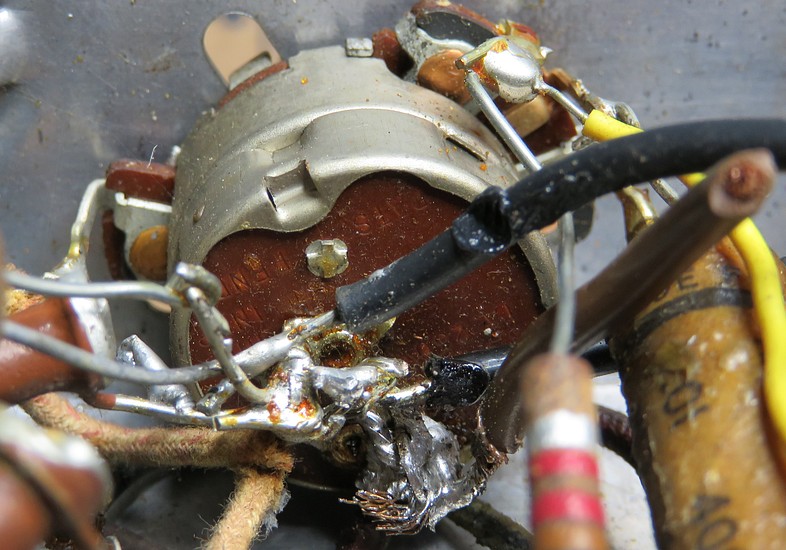

"Solder? We don't need no steenking solder!" |

|

|

|

Here's the exploded

resistor and what I think caused it. On the right, a new

line cord has been soldered to pin 1 of the rectifier tube.

(The number 1 on the socket is upside down in the picture.)

Some strands of wire from the cord are touching the chassis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This is as close as I

could get with the camera. There appears to be a burn mark

on the chassis where the wire is in contact with it. It was tested with an ohm meter

and it is a very good connection. Probably better than some

of the intended connections. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The small explosion flung a tiny molten ball of

solder against the chassis. |

|

|

|

|

So touching. This should be a Hallmark

card. |

|

|

|

|

|

| When I viewed the

On/Off switch connections I was "stricken dumb with

astonishment and amazement which bordered on stupification." |

|

|

|

|

| Two capacitors have been

removed just to be able to see this mess. How do you get a soldering

iron in there? |

| |

|

|

| Almost every component was replaced.

Teflon "spaghetti" insulates many of the leads, sometimes

needlessly. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Apparently, the way to replace the AC

cord is to cut the connections to the radio, then destroy

the KORD-LOK

strain relief by digging the cord out with a screwdriver.

|

|

| |

|

|

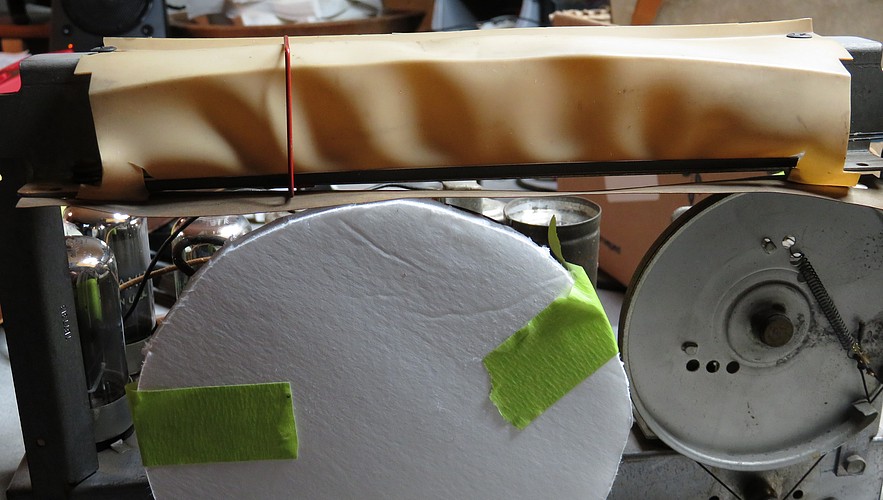

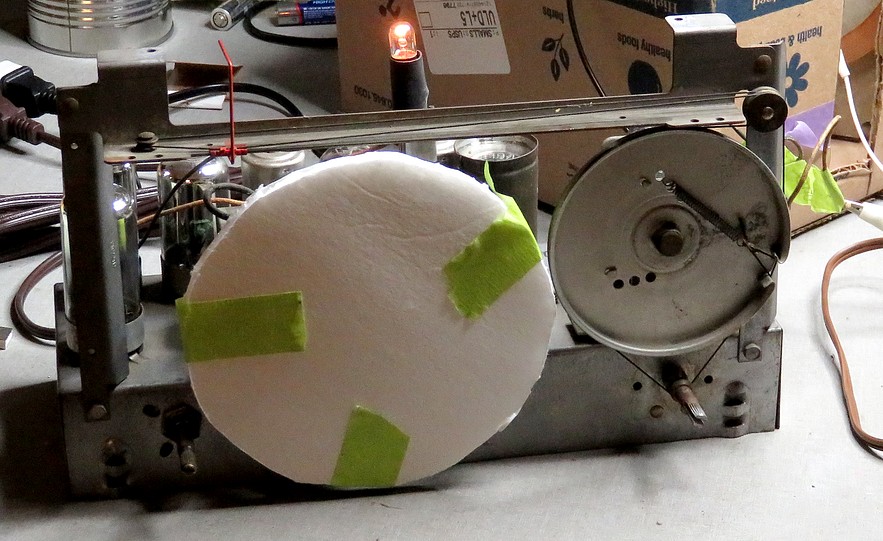

Crude replacements made

of cardboard and glue sandwiches, covered in

Polyurethane. They work as well as the real deal, the cord

is cinched down unbelievably tight but it's very gentle on

the cord.

I was going to use pop rivets

to hold them in place but reconsidered. The Motorola rivets

were probably used to keep the production costs down and the

repair costs up.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Revisiting the scene

of the crime. |

|

|

|

|

| The exploded resistor

has

been replaced. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

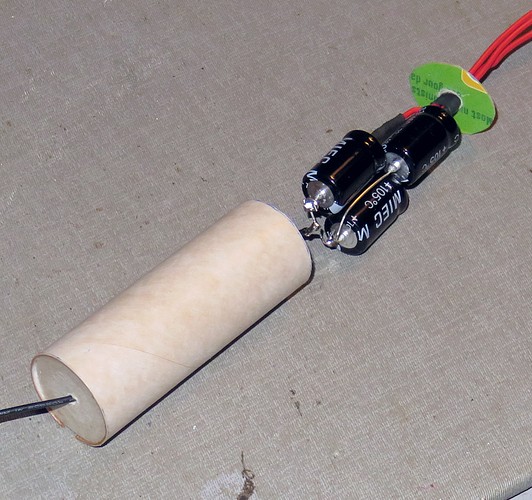

The new filter capacitor. The metal bracket from

the old one was used to hold it in place. "EMITS SHOWERS OF SPARKS." |

|

|

|

|

|

| Before we can turn the

radio on and try to tune in a station, we have to remedy

another problem. There is a piece of plastic that is

illuminated by the pilot light to make the dial face glow.

It has warped to the point where the dial pointer has to

bend as it is dragged across it. |

|

|

|

|

The plastic piece was

removed, and the radio was turned on. The pilot light, which

once worked, decided to burn out. It was replaced and the

radio was turned back on. The light came on but the radio

picked up nothing. It was as dead as a doornail.

I "shared the experience" with Andrea, thinking I would

impress her with my handiwork. The same thing happened last

year with the Westinghouse "Refrigerator Radio." I

couldn't turn around and look at her. If I found out she was

making that "loser" gesture at me I'd be humidified. |

|

|

|

|

|

LOOO-ZERRR! |

DOH! If I don't get this

set to work, all that sanding and

painting of the case was for nothing. There are seven coils

in this radio. What if one burned open? The IF cans were

checked before I started, but the oscillator coil is giving

strange results, as well as the 14C7 RF amplifier tube.

Pins 3 and 4 should read about 50K ohms each, but read wide

open.

I now have a bit of anxiety. What if I never get it to work? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This 10KΩ resistor is testing INFINITE

ohms. It is between pins 2 and 3 of the 14C7 vacuum tube. I

never gave a thought to it. It appears to be perfectly fine. Almost everything in the radio

was replaced, but I didn't even glance at this. |

|

|

| The 10K resistor was

replaced. The radio was turned on and emitted a loud

buzzing. NOW what?? On a hunch, I unplugged the LED light shining on the

radio and... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

IT WORKS!!! |

|

The buzzing was caused by the LED light bulb in

the work light! |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |